Running twice a year, the Big River Watch is an opportunity for citizen scientists to document the health of their stretch of river. Whether you’re a newbie or seasoned scientist, 15 minutes to fill in your app survey is all it takes to help your river.

We’re now looking back on the fifth edition of the biannual Big River Watch this year and dived into what the data is telling us about the state of the Trent and its tributaries.

Thanks to 1,700 participants surveying the Trent catchment, we’re analysing the most recent survey and uncover what people have told us about the rivers we’re looking after over the years.

Rivers boost our wellbeing

Starting with the good news: Spending time by our rivers makes people feel good. In September, 82% of commenters described feeling calm or happy. Others felt angry or sad about the poor state of their river. This is consistent with previous survey results.

Nearly everyone saw wildlife

Pollution

While wildlife offered a hopeful perspective, our citizen scientists also highlighted pollution issues in various ways.

The Big Stink?

Each Big River Watch recorded bad smells. Data shows that smaller brooks in urban areas seemed to be particularly badly affected by the stink. This will likely be caused by an increased concentration of pollutants. Looking at cities, Nottingham, in particular, seemed to suffer from smelly streams.

Various issues could cause bad smells and pollution more broadly, and these issues can compound.

We need better ways of working with farmers

Across all Big River Watches, silt and livestock pollution were consistently identified as the two most frequently recorded sources of pollution. While silt, likely washed off fields, can introduce excess nutrients, such as phosphates, it can also be indicative of pesticides and other toxins. Similarly, livestock can introduce silt and excess nutrients by poaching river banks.

Nature-friendly farming and nature-rich river buffers can offset or even prevent some of the damage caused. As part of our work, we are speaking to farmers. We know that farmers are on the frontline of climate change and at the mercy of an increasingly unpredictable water cycle. Moreover, the economic pressures are enormous, forcing some farmers to consider more intense farming methods. As part of this, we have called for better support and reliable incentives, so farmers can create more space for nature and operate within financially and environmentally sustainable conditions.

Algal pollution

Except for May 2024, algal pollution consistently ranked as the third-most frequent source of pollution. Algal blooms are fuelled by excess nutrients entering our rivers and are also encouraged by increasing water temperatures. Sewage and agricultural pollution can introduce phosphates and nitrates to our rivers and encourage algal growth, which can deplete oxygen levels, put freshwater species at risk, and choke out other plants.

Sewage

Similarly, sewage pollution continues to put immense pressure on our precious Trent and tributaries. Consistently, across all surveys, sewage and sewage fungus have been recorded by participants. Sewage frequently ranks as the fourth-most common type of observed pollution. The concern is not just harmful bacteria, such as e.coli or excess nutrients, particularly phosphates, sewage can introduce microplastics, forever chemicals, pharmaceuticals and other toxins to our rivers, both through treated and untreated sewage. It’s clear that water infrastructure is not meeting the challenge, neither in droughts nor deluges.

Observing the health of our rivers in a drought year

The September Big River Watch was the first to record drought. For the first time this year, sewage fungus outranked observations of sewage in our rivers, indicating that while perhaps less sewage washed into our rivers due to less pressure on combined sewer overflows. Nonetheless, the impact could still be observed and likely contributed to the algal pollution observed.

Litter

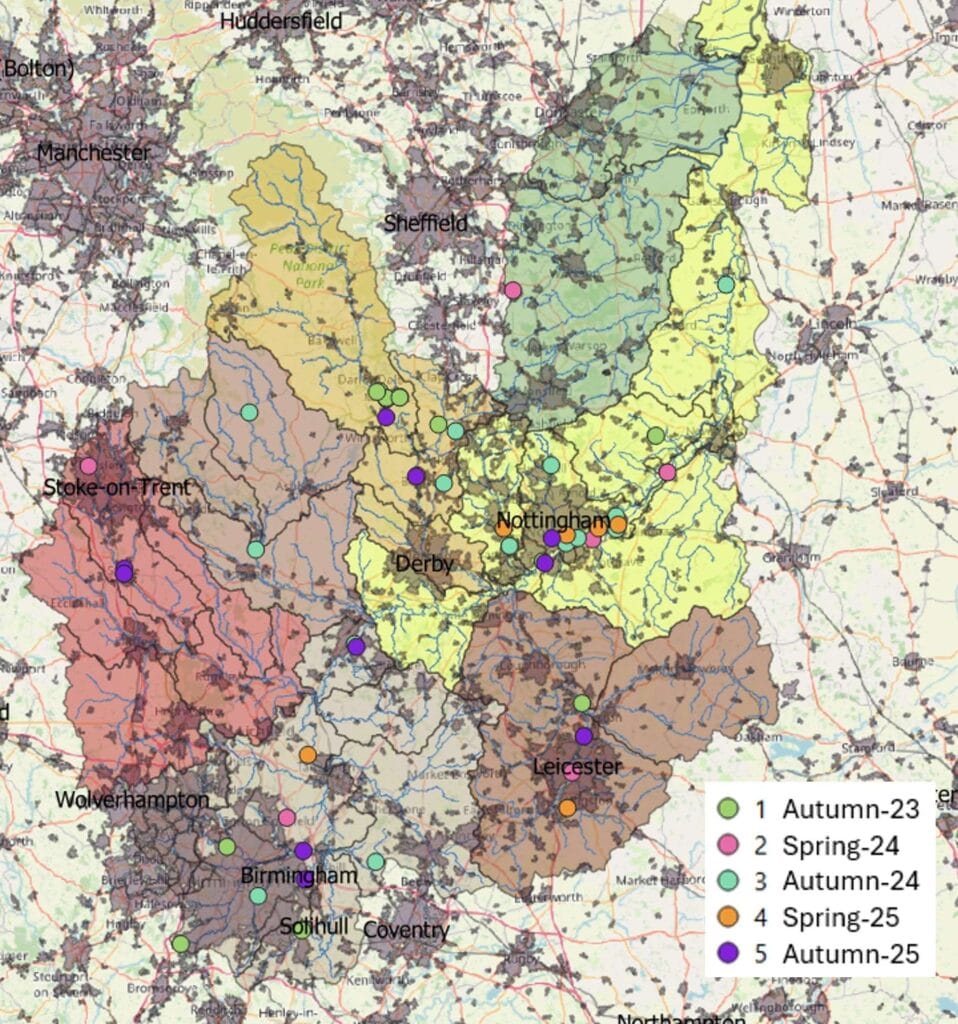

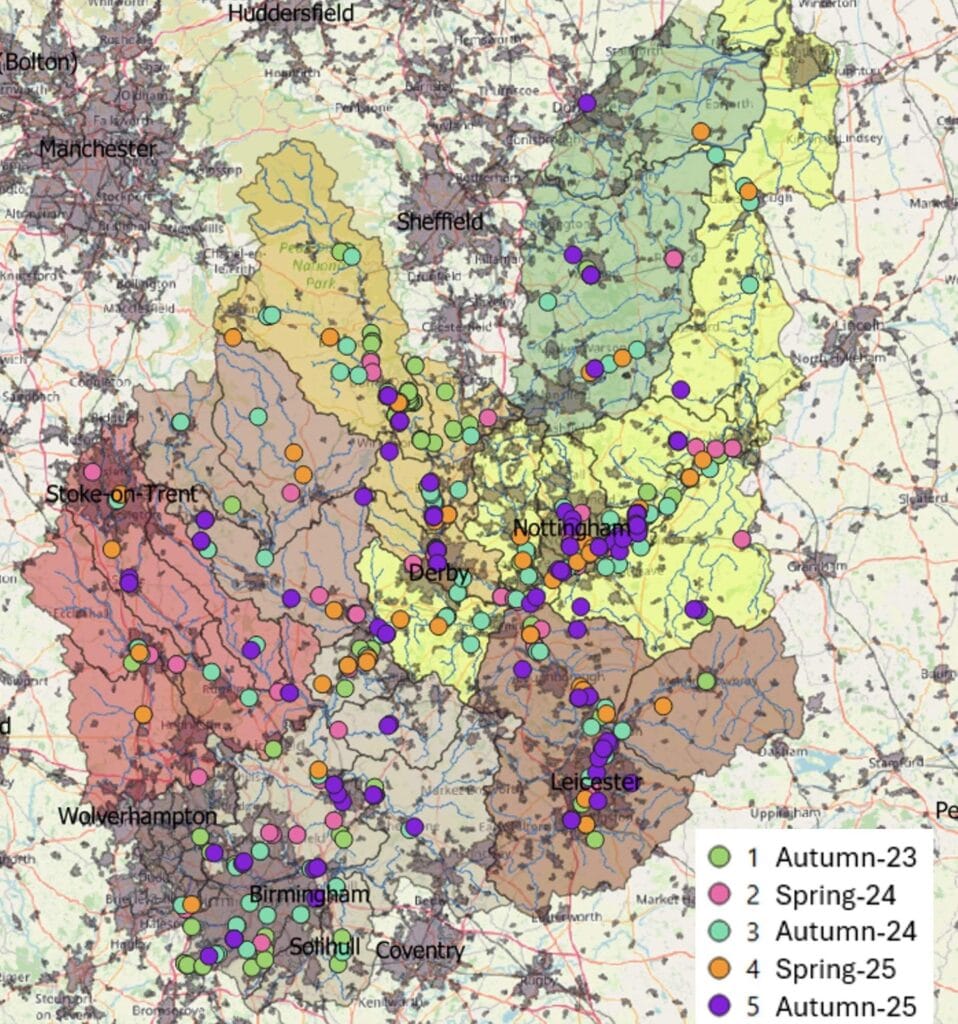

Over half of the participants recorded litter in September, particularly in urban spaces. This includes litter in the river and on the river banks. Take a look at the map and the 400 spots people have recorded pollution over the years. If you ever wanted to bring a pair of litter pickers to your local river, these are the places to go.

How can I help?

Enjoyed the Big River Watch? Citizen science is a fantastic way for non-scientists to gather vital data on the health of our rivers. This can include taking regular water samples to build a more detailed picture of river health over time. The idea is to spot irregularities and to gather information on changes in water quality throughout the year. The data can help us better understand levels of pollution, likely causes and what we need to do to address the issue.

If this is something you’re interested in, please get in touch via enquiries@trentriverstrust.org